Published on March 30, 2012

Tina Conroy’s voice cracks mid-sentence and mid-sob over the phone in the Veterans Affairs office (VA) of Columbia while a comforting voice reminds her she can stop if it becomes too painful. “We had nowhere else to go. We had no money, and it was me and my two children, and my daughter and her family.”

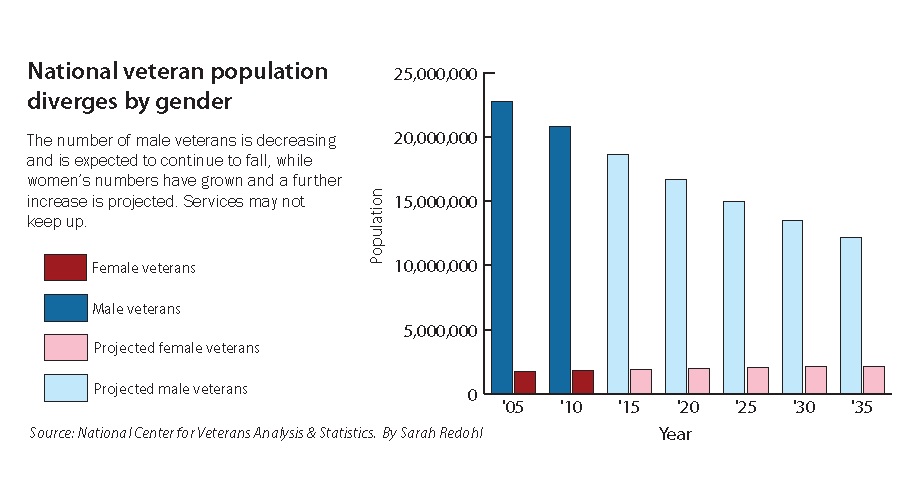

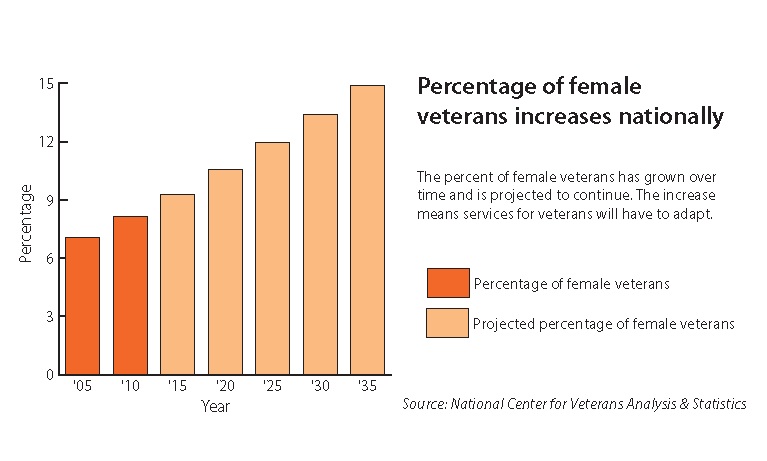

Conroy and her family have experienced frequent periods of homelessness since her service in the Coast Guard ended in 1983. Though homelessness is nothing new to the veteran population, as the number of enlisted women has increased from six percent in 2000 to eight percent in 2010, women are experiencing the issue of homelessness.

“We are starting to see women with children and women who no longer have a place, whether it be from them coming from deployment and finding out their world is different or the hard times from the economic situation,” said Sarah Froese, the VA’s Homeless Program supervisor–and Conroy’s comforting voice.

Though numbers of homeless veterans are difficult to pinpoint based on the periodic nature of homelessness and unreliable counting methods, Froese said she is aware of the trend. “Our female veteran population is twice as likely to be homeless than the male veterans.”

The method for counting homeless veterans in the past has been point-in-time counts, where the VA goes out into the community twice a year and counts the homeless they see. Of the total number, the VA estimates that 10 to 15% are veterans.

Froese said women returning from military service compete with other women who have identifiable job skills, while it may be difficult to translate their military skills into job experiences. Men’s skills might be more transferable, Froese explained.

Conroy said it was difficult when she left the military. “I had to find a job. I had to find a home. Without a job, you can’t have a home…so I’ve been dealing with the homeless thing for a while,” she said. Prior to 2010, Conroy moved from shelter to shelter, staying with family when she could. She had fewer resources available to find housing or stay in her own housing with reduced rent. Personal case managers, whom Conroy said have given her confidence to believe that she will not be homeless again, were not a well-known option, and were less available.

“In history, we have not seen a large percentage of homeless female vets before,” said Phil Steinhouse, director of Public Housing Authority in Columbia. “It’s a way underestimated problem in Missouri.”

Blake Witter, a coordinator for the VAs Supportive Housing program (VASH), said the large number of males in the military, compared to females, means that many services are male-oriented.

VASH is a nationwide program thats been available in Columbia for three years. It places veterans in permanent housing and provides them with amenities such as appliances, clothing and personal items. There are 70 vouchers available in Boone County without a specific time limit.Ten percent of those have been issued to women.

Witter tries to accommodate womens needs but, she said, sometimes the resources just arent there. Ninety-five percent of the donations we get are Axe and Old Spice. We arent getting Secret or Dove When people think of vets, they think of men, Witter said, but womens needs go well beyond the toiletries provided.

Cindy Stivers, the women veterans program coordinator at the VA, said women are also more likely to bring children with them. Of the 500 VA shelters across the nation, 300 are co-ed, but only 15 accept children. When youre talking about a single parent, thats a big issue you can facilitate the veteran, but what do you do with the children? Stivers said.

Conroy has lived in VASH housing for almost one year. She said shes happy with every service the agency provides. Now I have housing and we have a roof over our heads thanks to (VASH), and we have everything we basically need, Conroy said.

Permanent housing is a better option for families because it provides consistency for the children, according to Witter. However, both Froese and Major Kendall Mathews of Salvation Armys Harbor House shelter in Columbia agree that emergency shelters typically come first. We want people to succeed, so we promote the process of emergency housing, then transitional housing and then independent housing, Mathews said.

The recommended process may begin with emergency housing, but Steinhouse believes this is a difficult step for women. Shelters are set up for single men, not females with children, he said. For a shelter to accommodate women, it needs to have separate bathroom and sleeping facilities, locks on doors and increased security.

Welcome Home Shelter, a veterans-only shelter in Columbia with room for nine, just recently welcomed women,but is currently unable to house families. If you saw the layout, you would understand that it wouldn’t be feasible for children. Its not that they dont want to, but right now they dont have the facility, Froese said.

It is a two-story home with 8-by-8-foot rooms, and the common room is not much larger. The bathrooms and kitchen are shared, and there are no toys or safety precautions in place for children. It just isnt possible to put a whole family in that size of room, Froese said.

Harbor House puts families in private rooms, and offers rides to church and movie nights. Mathews said its important to offer services to keep families together.

When Conroy and her family became homeless, they ended up at the Salvation Army shelter in Jefferson City. Though it met the familys needs, Conroy said it was very difficult on her children. If (students at school) find out youre in a shelter, they put you down, Conroy said.

Often, women will leave children with relatives and go to shelters where they can be accommodated alone, said Witter. Women are very resourceful when it comes to providing for their families.

According to Mathews, there are other changes facilities can make to help make female veterans comfortable. Harbor House makes an effort to give men and women separate spaces. Stivers said such separation is important after sexual traumas some women experienced while in the military possibly making them uncomfortable sharing facilities with men.

I have been physically, mentally, and sexually abused, so its kind of hard to trust people and have a lot of men around me, Conroy said.

The military has taught women to adapt and overcome, and deal with it yourself versus asking for help Were trying to train the veterans when they come back that its OK to ask about these different programs, said Stivers.

Conroy said that everyone needs help, and she is happy to have found it. Now I know deep in my heart I dont have to go back through those situations and I know Im not going to be homeless again, Conroy said.